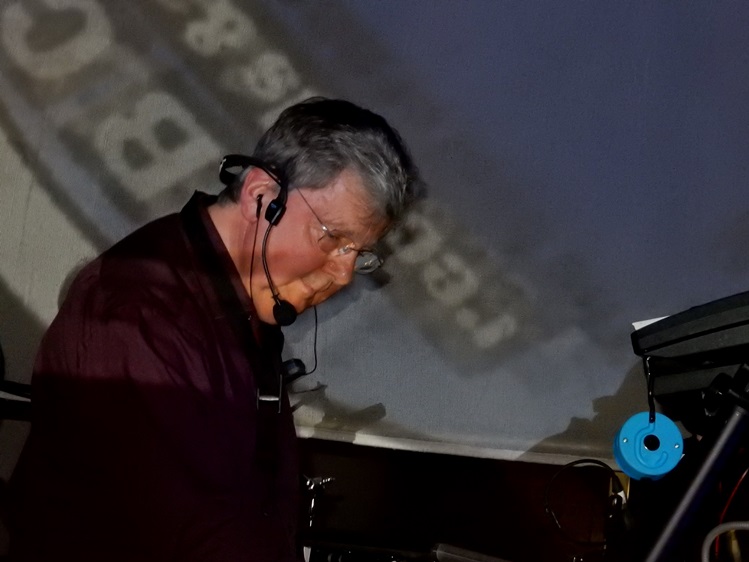

Electronic pioneer Peter Howell is best known for his period in the BBC as a member of THE RADIOPHONIC WORKSHOP.

His most iconic piece of music is the 1980 version of the ‘Doctor Who Theme’, originally made famous by Delia Derbyshire with her electronic realisation in 1963 of a composition by Ron Grainer. Howell joined in 1974, having already recorded a number of psychedelic folk albums with John Ferdinando under various guises.

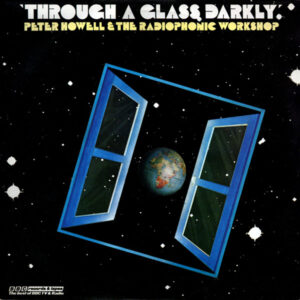

Using and abusing technology to create new sounds, for television, as well as music for ‘Doctor Who’ and other BBC programmes, Howell released the acclaimed album ‘Through A Glass Darkly’ in 1978. After The Workshop disbanded in 1998, Howell moved into academia, working as a lecturer at the National Film & Television School. Meanwhile in 2012, he published ‘Your Music on Film’, a handbook for film composers.

In 2009, Howell reunited with his former colleagues Paddy Kingsland, Roger Limb and Dick Mills under the baton of The Workshop’s archivist Mark Ayers for a special concert at The Roundhouse in London. It was the first time that THE RADIOPHONIC WORKSHOP had ever played live as a unit and interest from a whole new generation of fans was such that in 2014, they embarked on a UK tour which also included festivals such as Glastonbury, WOMAD and both Bestivals. More recently, this band of musical veterans have also performed at prestigious venues like The Science Museum, The National Portrait Gallery and The British Library.

‘Radiophonic Times’ is the new autobiography of Peter Howell, published by Obverse Books who also presented the world with ‘An Electric Storm, Delia, Daphne & The Radiophonic Workshop’ in 2014. With the ethos of The Workshop is still going strong since its formation in 1958, he kindly spoke to ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK about his ‘Radiophonic Times’…

What inspired you to write a book?

People had suggested someone from The Workshop ought to write a book, but I never thought I would be the person despite the fact I had written stuff previously. I was writing before I was composing, way back when I was 12!

But it was mainly because of the band stuff that came along and I thought it would be neat to do a book that was like a parallel thread of modern stuff to do with the band and historical stuff, bouncing the two off one another. It was a bit different so I gave it a try. I had to look for a publisher and Obverse have been great because I needed somebody I could talk to as I was a bit green to all this. It’s been good, I’ve enjoyed it.

Have you had formal training as a musician, what were your main instruments? There’s a photo of you with a lute!

Haha! My training is minimal, I’ve just got a fascination with all sorts of musical instruments. When I was back in Hove with my parents, I used to travel to Hayllars Music Shop in Brighton every month and they’d have something in the window that wasn’t very expensive that would make another noise.

So I’d accumulated all these different bits like a mandolin, lute, glockenspiel , all that stuff that makes noises. I got interested in doing it from the ground up, not from any training at all. John Ferdinando and I teamed up to do the ‘Alice Through The Looking Glass’ album and that used all these instruments I’d gathered.

As a part of the 60s psychedelic folk scene, how aware were you of the emerging electronic music movement. Did you ever go to clubs like UFO at the time?

No, I think this gave me a qualification to be in THE RADIOPHONIC WORKSHOP that I didn’t take any notice of anything else! I was completely oblivious to anything! *laughs*

I was just interested in making sounds and recording them. It never occurred to me I was part of anything of any genre, it’s only been after the event that John and I surprisingly discovered that we’d been labelled as “psychedelic folk”.

How did you become interested in using tape manipulation and electro acoustic sound design in music?

How did you become interested in using tape manipulation and electro acoustic sound design in music?

I was interested in producing artistic material from very clumsy machines, and they were clumsy in those days. I’ve still got my Revox down in the studio and it’s a very clunky device *laughs*

That’s what I was fascinated with… the other day, a book that I had very early on that I’m very sorry to have lost, you’d be very shocked at how old fashioned it looked, a sound recording manual produced by people like Abbey Road Studios and the like. All the machines in it looked as if they were from the Second World War with big Bakelite knobs on everything, men in very baggy trousers with turn-ups! *laughs*

It was like a bible to me, I used to look at it all the time. I was interested in the idea of producing an artistic audio something out of the most unlikely things. On ‘The Walrus & The Carpenter’ from the ‘Alice Through The Looking Glass’ album, we actually used an old telephone and wired that up to record through the mouthpiece.

In those circumstances, you experiment with stuff and it’s the result of the experiment that inspires you to write the music, it’s not the other way. The more academic way of doing music is to acquire a skill and then look for a way to use it, whereas this was round the other way, acquiring a sound to see what can do with the sound to write the music. I regard it as “inside out” composing rather than “outside in”.

So all this interested to you applying for a job as a studio manager at the BBC?

Yes, that’s right. In the interview for that, I was chatting about what I was doing with my Revox and all the stuff, I think that got me the job.

How did you come to join THE RADIOPHONIC WORKSHOP?

There was a senior studio manager who was at the mixing desk, I was the junior studio manager playing tapes and LPs. I got given tapes to play with blue leader on them… at Broadcasting House, the leader was yellow for the cues and red for the end. These tapes that had blue leader on them, the sounds were amazing! So I asked about these tapes with the blue leader on them and I was told “that’s THE RADIOPHONIC WORKSHOP”.

By coincidence, I was doing some amateur dramatics at the BBC who had their own theatre group and while we were at The Cockpit Theatre in Paddington, somebody mentioned that they had a load of synthesizers upstairs. In those days, there was basically only one marketed synthesizer which was the EMS VCS3 and they had three of them that these days would set you back about £10,000! *laughs*

So me and this other guy played around on these synths and we did some music for the show. When somebody at the BBC heard these, they suggested that I should be in THE RADIOPHONIC WORKSHOP. In the end, I applied for an attachment for three months and that’s how it started.

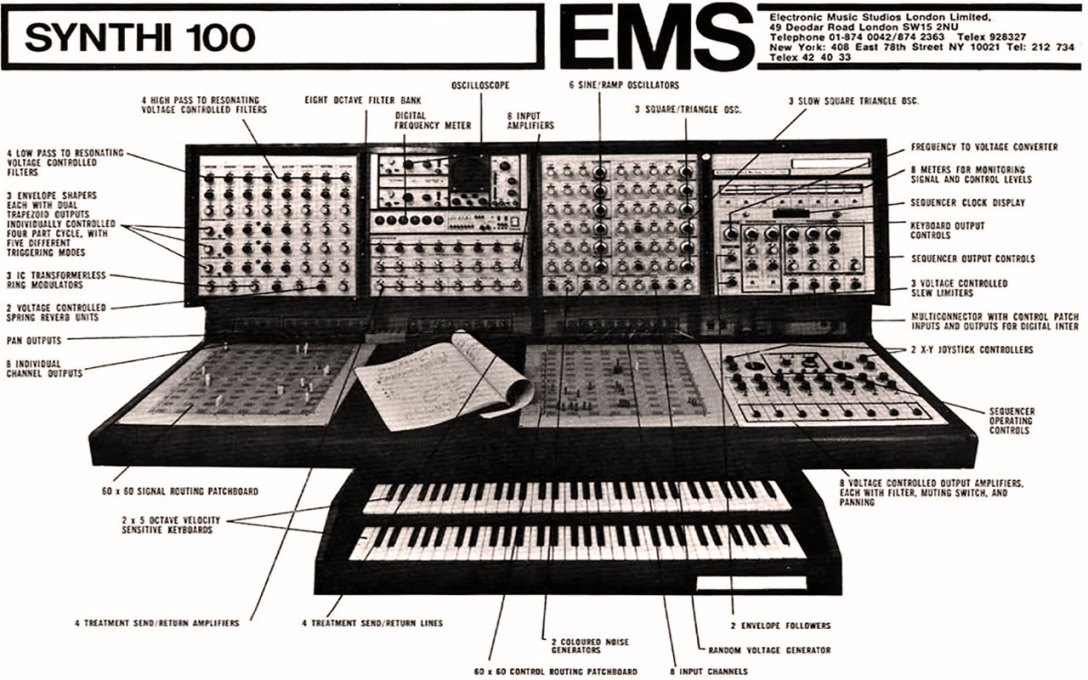

What did you think when you saw the huge EMS Synthi 100 Delaware there?

I thought “maybe I should start with the small one first”! *laughs*

It was enormous, it was the size of a Welsh dresser so I graduated to it later on. It didn’t fulfil its early promise for me I think you could say.

It was a very big device, it had a gigantic number of controls on it, some things that it did, nothing else did at all and it had a 256 note sequencer which was pretty unheard of at the time. It had this wonderful matrix switching panel which was really groundbreaking.

But the problem with the Delaware was however hard you tried, you could never really get it to make full sounds, it was a bit thin. The very front of ‘The Astronauts’ LP track is the Delaware, there’s a sequence of notes that I knew it could do well. There’s another track called ‘Secret War’ which has sounds made on the Delaware and as long as you knew what it was going to give you and not try anything else, it was absolutely wonderful. I didn’t find it was something you could use for a whole piece.

The VCS3 and AKS were loved by musicians but maybe EMS never made another synth as good as those again because the Polysynthi was horrible, it never made a decent sound no matter what knob you turned and Vince Clarke said it was “the worst sounding synth ever made”…

I think it was a mixture of a lot of things and I think it had a lot to do with the filter. When you look at subsequent synths, the quality of the filter was very important, especially one that could have a bit of drive in it for some “oomph”. Things like the Moog were known for their filters and that was probably the shortcoming of that machinery. But EMS really were groundbreaking at the time and if it did nothing else, it introduced us to the fact that here was a machine that was making sounds that you had never heard before, you genuinely hadn’t, that was the excitement of it. Now that’s impossible to say these days.

There was also the possibility of not being able to get “that sound” again!

Haha! You’re dead right there! It’s all very well for everybody to love the old days and get all nostalgic, but there’s one thing I’m not nostalgic about and that’s machinery forgetting what it was doing yesterday! These days, the ideas of memories and coming back to something to carry on working is wonderful, everybody takes it for granted. I was so paranoid at not being able to get back to the same sound again, I would either work through the night in order not to walk away from it or alternatively, make a cassette recording of me dictating all the settings so that I could come back to them, that’s where we were at! *laughs*

So I can be forgiven for being a big exponent of laptop based stuff and I’ve got some really favourite high level software that I use, this is all nirvana to what it was! *laughs*

There was this mysterious dial marked Option4??

Haha! Yes, that was on the Delware! There were no wires attached to it, it was simply so that the facial panel could look more symmetrical! *laughs*

But we did use it because there comes a point in “your tweaking of the tweaks” as it were, some people have what I call ‘finishitis’ who, through lack of experience, can’t finish… they don’t know when something has been completed, so they assume there is always something else you can do to it.

So that’s a habit that you’ve got to get of very fast if you’ve got deadlines. Some of the BBC producers loved coming across to Maida Vale because it was a trip out from Broadcasting House or Television Centre and they could put their feet up and get into doing stuff. But there comes a point when you feel like saying to them, “why don’t we give it a bit of Option4 to finish it off?”, you know! *laughs*

You were often considered to be The Workshop member who had a pop sensibility as there was a move from the more music concrete approach to straightforward synthesis. Were you still encouraged to be experimental?

Well, Paddy Kingsland definitely when I arrived at the Workshop was the person who was associated with pop and rock. His output really put electronic tune making on the map I think.

He was able to use synthesizers in such a pure and direct way that his style revolved around being tuneful as well as being electronic. If I did go in that direction, it was inspired by his work really.

As far as I was concerned and it still applies to this day, I am equally experimental and melodic. Some of the latest music on my website has got that sort of trend. You will find there is experimental stuff at the front of a track and it then crystallises into more thematic stuff.

I think it’s a perfectly reasonable question to ask how much was dictated by what the directors want, we were a service department, weren’t just toodling around and being paid for it. We needed to supply programmes with what they wanted, so you are guided by what the programme needs.

‘The Astronauts’ needed a big theme for the early space race, so that was an example of where you could be experimental in a lot of soundtracking satellites talking with one another and thematic stuff which is more melodic. All the way through, I’ve tended to try and ride both horses at once

Your work on ‘The Astronauts’ in 1978 was very Wendy Carlos meets Vangelis, did they inspire you?

I think panic was inspiring me! *laughs*

In the book, it refers to how ‘The Astronauts’ came about. I was unwisely persuaded to run a session with live musicians because there was a lot of money backing it and probably the first and last time it was available for music. It was a European-wide venture and there was money coming in from everywhere, so it was decided to spend it on musicians. It was passable, it wasn’t awful but there was nothing special about what we did.

By the time I got back to the studio upstairs, I hated every split second of it frankly. I wanted to add some synth lines and the deadline was the next day. So I started fiddling around on the ARP Odyssey and I came across a random control voltage effecting a filter at the same time as an automatic repeated note. So it was going “dah-dah-dah-dah-dah” but every time it sounds, the filter is in a different position.

I added some tape echo to it and discovered that if your tape echo was slower than you would normally expect, you could get the echo to occur after the following note. So “note1” sounds, but the echo doesn’t occur until after “note2”. So if “note1” and “note2” are “da-dah”, then it goes “da-dah-da…”. So if you progress that through to a series of runs, you get semi-quavers appearing in between the runs in an interesting galloping sort of effect. That was the basis of the track, it was genuinely experimental as far as I was concerned. I didn’t know really what was going to happen. Once I got that bassline, that was it. So using this inside-out system, once you get a sound that is strong enough, everything else follows. It’s like a blossoming flower.

Do you think that music was influential on acts like TANGERINE DREAM because they started to sound like what you did on ‘The Astronauts’ when they went off to do all that soundtrack work?

I occasionally heard stuff that I thought might have had associations, but we didn’t imagine we were connected to the outside world *laughs*

We were like inhabitants in a computer game really, existing in our bubble and we never met the public who heard our music on these programmes, we only ever met the directors of the programmes who came to us. So it was a hermit-like existence. You read a lot of people have been inspired by The Workshop but it was quite surprising to us as we were just doing our thing *laughs*

Is it true there was a rivalry between you and Paddy Kingsland at The Workshop?

Oh the rivalry was NOT on Paddy’s side at all, but it was slightly on my side! It wasn’t his fault, but I did feel I was regarded as a slightly less good Paddy Kingsland. I had ability on keyboards, it wasn’t massive and I had talent, but it was evenly spread across guitars and keyboards *laughs*

I didn’t think my keyboard side was represented enough in people’s opinion of what I could do at the BBC, so that was one of the reasons why I decided to do the ‘Through A Glass Darkly’ album, the whole of the first side of which relies quite heavily on keyboard work, not just synths but a Steinway, I went the whole hog *laughs*

If there was rivalry there, it was entirely my fault but I felt I needed to up my game a bit!.

Yes, there’s nothing like a bit of creative tension…

…absolutely!

What are the challenges of writing incidental music compared to a theme? Did you compose to moving images, have a brief or story board?

You basically look at rough cuts of the film, story boards are no good at all and scripts aren’t much good either! When I was doing ‘Doctor Who’, one of the most disappointing things looking back is the ludicrous number of trees they cut down to make these redundant scripts that they’d send everybody, great fat ones! The pink one was the shooting script, the yellow one was the editing script, every single episode, there was another one!

And I didn’t look at any of them! What’s the point? The important thing is what’s the picture I am actually writing to. Until I got the rough cut, I didn’t waste the time of actually doing any work on it. Because I respond to the film itself, I didn’t want to fire all my ammunition too early. You need to keep your powder dry I think is the expression *laughs*

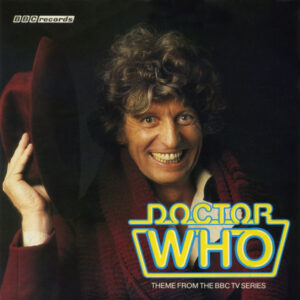

What do you remember about reworking the ‘Doctor Who Theme’? Was there a weight of responsibility?

It was tampering with an institution and I did it with a lot of trepidation. I agreed with Brian Hodgson and ‘Doctor Who’ producer John Nathan-Turner beforehand that if I and others didn’t think it was going well, we would actually shelve it and nobody would know it was even being done. So we had to be quite secretive about it. I remember when I had the bassline and one or two bits, I went to Paddy as he was doing some trials of incidental music for John Nathan-Turner and asked him “ought I to continue with this or not?”; he thought it was alright *laughs*

It gradually evolved and took me six weeks overall. I tried lots of different bits of gear in The Workshop. One of my concerns was people could meet in the pub afterwards and say “oh, I know what he was playing for that! It’s a so-and-so and it’s the third preset along”, I hated the thought of that happening. I still hate the thought of that happening to this day! *laughs*

So I went out of way to find unexpected uses of bits of gear. The CS-80 was only ever used for the bassline, nothing else. The ARP did the “oooh-wee-ooooo”, the Roland Jupiter did the middle eight with a tremolo sound because it’s got a good arpeggiator on it and so it went on, every part really was from a different place.

Some of it was quite a lot of work. For instance, towards the end of the opening theme, there is a sound that is like a Catherine Wheel, a “swoo-swooosh-schwhhh”, that was a whole session on its own. It was done with different multitrack tape using match flares and all sorts of things old style, cutting the tape up, feeding it back through echo, looping it, all the rest of it. I’d master it onto a ¼ inch stereo tape and play that onto the main multitracks. So there were bits that were like sub-contracted out to a different session and then brought back in again.

There was a lot of work involved in trying to get an organic sound environment. I was pleased that I sort of got that because it’s something that Delia Derbyshire had with her version. You’ve got to admire her with what was at her disposal, she really did invent a whole sound world for that piece. I was very keen to try and do the same thing.

One of the most difficult sounds to emulate would have been the attack of the bassline?

That’s right, if you listen to the bass on mine, it has exactly the same “gulp” sound in front of each phrase that Delia had, and I make no excuses about being inspired by what she did, because that was such a lovely effect, almost like the bass was tripping over itself. It’s not four square predictable, it’s got that “lurch” feel to it that I really liked. I did that by reverse reverb which is taking the bassline that was played accurately along the way, turning it upside down and playing it into reverb, re-recording that and turning it upside down before setting it back a tiny bit, so that you have lead-up sounds to the bass notes. That way, you’ve got this feeling of tripping over.

You’re doing all this tape manipulation stuff, but then comes the Fairlight which makes it all much easier?

Moments like that are quite pivotal. If I had been somebody who utterly loathed the idea of digital, that would have been the end of my career frankly. The way things were going, they were heading in that direction. Oh I loved it, several of us loved it too much and then Kate Bush comes along with her ‘Never For Ever’ album and I felt like never touching it again. All the Fairlight stuff was so wonderful and fabulous on that album, so that brought me up a bit short!

I realised you can’t expect to survive on one bit of gear, it’s that same as going back to the Delaware. When this wonderful new thing arrives, you think “oh my God, this is the end of life as we know it”, but it isn’t and it did add lots of very interesting things. But you have to be proportionate I think.

You demonstrated the Fairlight to school children on TV in 1982 and with its “smaller box than you’d expect for a computer”, it’s all very ‘Look Around You’… what do you remember about doing that?

It’s very twee! Whenever you do television, you realise how utterly false the whole thing is, however live it might be! Everybody is so aware of getting it right and doing it like you did it in rehearsal and all the rest, it was not my greatest hour! *laughs*

Of course that clip got spoofed with you inventing drum ‘n’ bass… *laughs*

Yes, it was nothing more than we all deserved! *laughs*

What makes it funnier now is the indifferent girl at the end obviously comes over not very keen on drum ‘n’ bass…

I didn’t find out who did it, but I became aware of it through a student, at the film school I taught at, who sent me the link. But then the day after, he sent me an email apologising for sending it to me thinking I’d be terribly upset. But I told him I’d never laughed so much in my life! It was hilarious! *laughs*

Were there any instruments in The Workshop that you never got on with?

I had an arms-length relationship with the Delaware but I got on with it, but I never really went for the PPG or the Oberheim. With the PPG, you felt you were already using the Fairlight and it’s doing it better. Meanwhile similarly with the Oberheim, people were saying they were very beefy sounds and they sort of were, but I don’t think it warranted the effort for me.

But when we came onto stuff like the rack-mounted gear, something like the Yamaha TX816 which was eight DX7s in a rack was fantastic. You could do the most amazing things, sometimes playing all eight at once, some slightly detuned, all sorts of things. A lot of the Yamaha and Roland gear was generally speaking, pretty up there. I didn’t go for Akai samplers when virtually the rest of the planet was going for them, I liked the Roland library and their samplers with the standalone monitors so you had a little bit more information about what was happening, you weren’t looking through a little window all the time, it was things like that.

We were very idiosyncratic, you could find somebody in The Workshop who liked something you disliked so it really didn’t matter as each of us had our own projects, we were actually hardly collaborating at all.

How did you get on with FM synthesis programming on things like the DX7 and TX816?

John Chowning, the guy that invented FM synthesis actually game to see us. I liked it a lot but as with everything else, I liked “playing the whole room” so I didn’t like relying too heavily on one thing for total solutions, because I actually think it leads to sound a bit vanilla for me.

You use the DX7 live as your keyboard controller, what’s that triggering?

My keyboard is controlling laptop based synths that are local to me and occasionally via MIDI lines, synths that are with the others. And the same goes in reverse, it sounds ludicrously complicated but we’ve got it down now to a reasonably workable solution.

Mark Ayres is the hub, he is responsible for the timeline, the video on it, click tracks that all come out to us via Ethernet connected personalised monitors, so each of us have control of sixteen tracks just for our monitoring. It historically goes back to our concert at The Roundhouse in 2009 when we relied on The Roundhouse to provide our foldback and never again, because it was so difficult.

We realised that our sort of material is so varied that you need to be far more specific about your foldback. If you are a rock band and basically using the same line-up for most numbers, you can virtually predict whatever your set-up will be ok when you play the next thing. Not for us, we’ve got so many different sorts of material that we needed a customised way of dealing with it. That describes it roughly.

You use an Akai wind controller on stage too, are you trained in wind instruments?

It goes back to Hayllars and buying lots of instruments. I learnt recorder, penny whistle and I learnt some clarinet and flute. The fingering on the wind controller is most like the flute because you can actually choose what fingering you have, I really enjoy it. I’ve also got a Launchpad Pro matrix that I use for more sound based stuff and I play guitar as well.

How have you needed to adapt the stage set-up for touring purposes and practicalities in live shows?

One thing that came out of The Roundhouse concert for me was ways not to do it. I really didn’t like the experience, one of the things that I thought was absolutely stupid to have done was to put the synth keyboards in the way of me and the audience. You’ll see now since when we went out on tour, I had the keyboards placed sideways so that I have an open view of the audience. When I play guitar or wind controller, I am towards the audience and for me, I’m playing to somebody. At The Roundhouse, I could have been in a study somewhere, I just felt totally disconnected. So that’s one thing that I’ve appreciated doing, that’s worked and Mark has done the same so we are backed onto one another.

THE RADIOPHONIC WORKSHOP have been performing as a live entity for some time now in the last few years. But being mature musicians, touring is not a natural thing to want to do for the first time? *laughs*

No! Cliff Jones, our manager kindly realised that we wouldn’t be sleeping in the van! *laughs*

So, the accommodation we’ve had has been quite good, it’s not the Hilton but they’re comfortable hotels. We have probably spent an inordinate amount of our earnings as a band to making sure we’re feather bedded *laughs*

Mark Ayers has mentioned that it could all be done on laptops but visually wouldn’t be very exciting for the audience?

One of the reasons I turned round and also that I’m playing different instruments was to help with the visuals. I’m not an enormous fan of the presentation style of KRAFTWERK these days, to me they look like a series of chartered accountants standing behind their laptops. So I didn’t really want that to be the way we came across.

Also, we’ve got a live drummer Kieron Pepper and that made an enormous difference right from the start… it also made it a bit more complicated but probably it ups the excitement value, certainly when we get round to doing our finale which is a very extended nine minute excursion which lands into the 1980 ‘Doctor Who Theme’ and I think that proves the value there. In fact, we have two drummers, Bob Earland who is an electronic wizard but also a drummer who was trained by Kieron so the two of them are occasionally drumming together.

There’s also the video projections?

We’ve got videos for everything bar one thing and we regard that as quite important as our audience from the word go were looking at their television so used to hearing our stuff with visuals. I think it would be quite difficult for them to suddenly have nothing but us playing on stage. So we’ve kept that in mind throughout, but it does make it a great deal harder to do, but it’s what the audience enjoy.

Mark has so many good suggestions in problem solving along the way which has been invaluable, his input has been phenomenal from the start. There have been a few ideas where I’ve been doggedly trying to get it to work and there comes a point when somebody else in the band says “why don’t we stop doing this because it’s not working?” *laughs*

For instance, using vocoder live if there’s too much coming off the drum kit, not to be recommended at all! *laughs*

You’ve influenced a whole variety of musicians, producers and DJs, who out of the more recent generation do you think best encapsulates the spirit of The Workshop?

There’s tons of stuff but I’m really bad at making mental notes of people, because part of the problem is I don’t get hooked on one person. I am full of admiration of what they are all able to do, I feel in the stuff I’m writing now, I’m just a member of their band to a certain extent.

Nobody is pretending that pioneers can carry on being so, they are the people treading the new ground and there’s fabulous stuff around. And it’s not just pure electronic stuff, it’s also production values and some things are quite extraordinary. It’s what keeps me going really, I’m fascinated by how people are achieving things. I love Tim Exile’s stuff, he’s somebody who uses technology live in a completely off-the-wall spontaneous manner, he’s helped Native Instruments develop a few plug-ins, one called Mouth which I use.

What have been your favourite pieces of work in your career?

When you ask composers what are their favourites, they may choose things they were up all night writing which means they are much more memorable.

For me, it’s often stuff people probably wouldn’t think twice about, I love what I did for a Channel 4 series called ‘Reality On the Rocks’ with Ken Campbell, the comedian trying to discover the details involved in quantum physics; in the 90s because of the producer choice internal marketing policy within the BBC, we were able to offer our services to other networks.

Obviously, I am delighted with the success of the 1980 ‘Doctor Who Theme’, because it’s been a calling card for me, I can’t possibly not mention that and it was very enjoyable to do.

‘The Astronauts’ too but we are going a long way back, there are things in the meantime that you are pleased with for different reasons. I did the title music for ‘Cardiff Singer Of The World’ for a couple of years and that was all done on glass rims, you get pleased with things for particular reasons.

ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK gives its warmest thanks to Peter Howell

Additional thanks to Stuart Douglas at Obverse Books

‘Radiophonic Times’ by Peter Howell is published by Obverse Books, available now in paperback or electronic formats from https://obversebooks.co.uk/product/radiophonic-times/

https://www.peterhowell-media.co.uk/

https://twitter.com/peterhowelltalk

A ‘Radiophonic Times’ playlist compiling a variety of works throughout Peter Howell’s career can be heard at https://open.spotify.com/playlist/1lvTOEdEUGcucgGRc6zhFE

Text and Interview by Chi Ming Lai

12th April 2021

Follow Us!