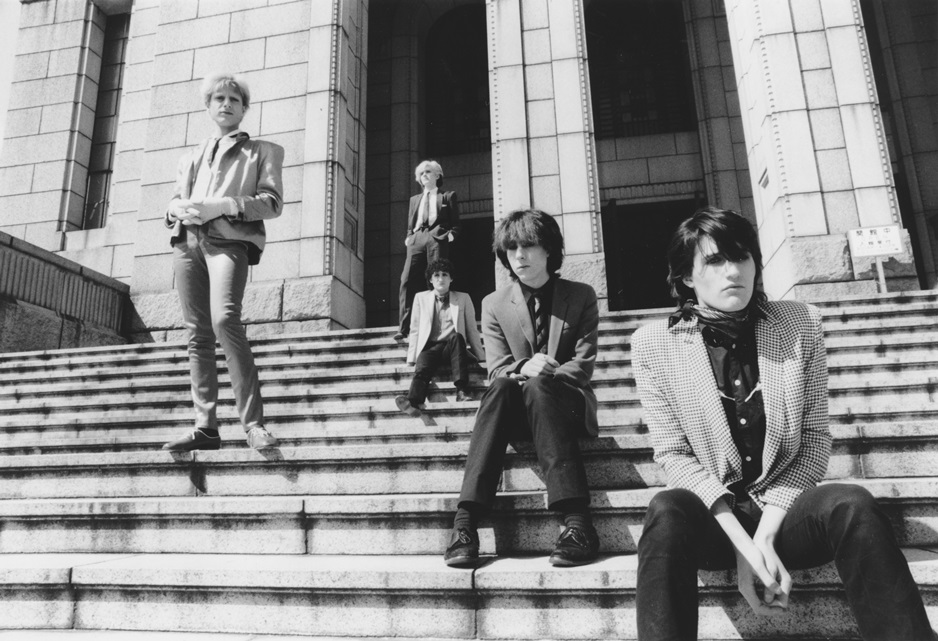

Steve Jansen was just 18 years old when he recorded his first album as the drummer of JAPAN.

Founded with his brother David Sylvian and school friend Mick Karn in 1974, the trio soon recruited Richard Barbieri and Rob Dean before JAPAN were spotted by noted svengali Simon Napier-Bell who had managed Dusty Springfield and a pre-fame Marc Bolan. Signing to Ariola Hansa, JAPAN eventually found their sound with the sophisticated art rock of their third album ‘Quiet Life’. Decamping to Virgin Records in 1980, things began to gain momentum for the quintet with their fourth album ‘Gentlemen Take Polaroids’

, as the arty poise of the New Romantic movement began to take hold within British popular culture.

However, JAPAN were moving towards a more synthesized sound, with Sylvian and Jansen now also contributing keyboards. This ultimately led to the departure of guitarist Rob Dean, but the remaining quartet went on to record what many regard as JAPAN’s most accomplished long player ‘Tin Drum’. ‘Tin Drum’ was to become their biggest seller and assisted by a two prong campaign also involving their former label’s various reissues, JAPAN enjoyed a run of 6 successive Top 40 singles in 1982.

Despite their success, personal and creative tensions led to JAPAN disbanding at the end of their year. Jansen remained on good terms with his brother and his bandmates, particularly Richard Barbieri. While working with them on their solo ventures and in various combinations under the monikers of THE DOLPHIN BROTHERS, RAIN TREE CROW, JBK and NINE HORSES, there was also Jansen’s long standing friendship with Yukihiro Takahashi of YELLOW MAGIC ORCHESTRA.

Jansen did not actually release his first solo album until ‘Slope’ in 2007. Featuring a number of guest vocalists including David Sylvian and Joan Wasser, the pair’s striking electro-blues duet ‘Ballad Of A Deadman’ was one of the highlights. His second solo long player ‘Tender Extinction’

was an evocative blend of songs and instrumentals which developed on the template laid down by ‘Slope’. But while mixing the record, Jansen came up with the concept for ‘The Extinct Suite’.

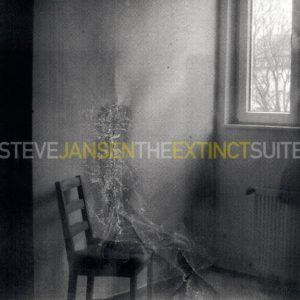

Not a remix album as such, the more ambient and orchestral elements of ‘Tender Extinction’ were segued and reinterpreted with new sections to create a suite of instrumentals presented as one beautiful hour long piece of music. A gentle blend of electronic and acoustic instrumentation including piano, brass and woodwinds, ‘The Extinct Suite’ exudes a wonderful quality equal to Brian Eno or Harold Budd.

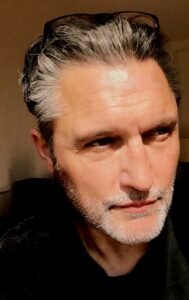

Steve Jansen kindly chatted about his varied career and vast catalogue of work.

‘The Extinct Suite’ is a new album but sort of isn’t… how did the concept come about?

I felt that there was a lot of musical content behind the vocal tracks on ‘Tender Extinction’ that leant itself to being reinterpreted as instrumental music. My aim was to extract these elements and link them into a ‘suite’ which meant composing some new pieces as well as, in some instances, significantly altering the original source.

Was there a feeling that ‘Tender Extinction’ could be taken further?

In the sense explained above, I felt there was more to be explored.

Do you feel you now have more in common with classical composers in wanting to explore variations on a theme?

I doubt it. I explore sonics and arrangements and spend many hours sound designing and keeping an open mind as to where it all might lead. I don’t have many musical disciplines.

‘Worlds In A Small Room’, ‘Swimming In Qualia’ and ‘A Secret Life’ are just some examples of your other ambient work, how did you become interested in that area and which particular artists or composers have influenced you?

I like the effects of calm and dissonance and subtle change, elements that have been present in most of the music I’ve been involved in.

I don’t really listen to other people’s music anymore because I find I’ve no real use for it, but there was a time when I would enjoy ambient releases during the 70s / 80s by all the knowns of the time.

How do you differentiate your approaches for instrumentals as opposed to songs? What do you get out of instrumental work that you wouldn’t get from writing a song?

Songs usually require more structure and chordal shapes. Ambient music is as I’ve previously described and affords you the chance to deviate from the path and explore things on a whim.

In THE DOLPHIN BROTHERS with Richard Barbieri, you were recording perhaps more conventionally framed songs, how do you look back on that period?

It was a lost period. We found ourselves in a bit of a limbo. We came from a pop background and, unlike today, in order to survive in the music business you needed label backing, and the business of music was dominated by labels acting as moneylenders that wanted to see big returns. Without being a part of that machine you would disappear altogether. Richard and I were signed and dropped by Virgin (and their subsidiaries) 4 times in all and during that time we had to wait for technology to significantly move the goalposts.

Your 1986 single ‘Stay Close’ with Yukihiro Takahashi was a fabulous one-off, do you ever regret that the two of you never did a full joint album together back then?

We did an album under the name ‘PulseXPulse’ but it was more aimed at the Japanese market. Yukihiro is not very exportable and he plays into his own market because that’s what serves him best. I’m sure we could have made a collaboration album in the vein of ‘Stay Close’ but it would have been very much of its time.

You’re a proven competent vocalist but for your first solo album ‘Slope’, you brought in guest singers, a tradition that has continued with ‘Tender Extinction’… what was the ethos behind that?

I beg to differ. I don’t enjoy working with my own vocals, it’s much nicer for me to be able to write music with vocalists whose singing brings an unexpected dimension and inspires me to bring out the best that I can from the collaboration between myself and them.

You’ve always been more than a drummer and you utilised keyboard percussion on ‘Gentlemen Take Polaroids’ and ‘Tin Drum’; what attracted you to experiment with that aesthetic?

During JAPAN’s days I was often asked to play keyboard parts that required precise timing (pre-computers of course) and this was my foot in the door into keyboards… that, and the marimba.

During the ‘Tin Drum’ period, you had access to the then state-of-the-art technology like the first Linn Drum Computer and Simmons Drums. How did you find those to use?

At the time the Linn Drum Computer was exciting to work with, however the Simmons Drums were another matter. Very limited sound and extremely physically hard to endure due to the fact that the drum heads were made of riot shields which had no give and created shockwaves that caused finger joints to swell dramatically.

You had co-writing credits on ‘Visions Of China’ and ‘Canton’. Had these two originally been your ideas?

That would have been put down to the fact that what I was doing rhythmically played a bigger part than usual in the inspiration and direction of the songs. But in reality I don’t think it was the right way of doing it. I think all JAPAN’s music was methodically arranged by each member and warranted some co-writing credit however small.

Richard Barbieri still uses analogue technology alongside modern equipment and techniques, do you have any continued interest in vintage equipment?

Not really. Nor vinyl.

The 2015 release of the 1996 concert recorded in Amsterdam as the ‘Lumen’ EP was a reminder of what a fantastic combo of musicians you, Richard Barbieri and the late Mick Karn, with the addition of Steven Wilson, were. Do you miss full-on live work, especially as these days you appear to be more computer based?

I do miss it. I like performing live but I really don’t enjoy the cumbersome aspects of putting shows together where there are budgetary restrictions. There was a time when I would try to put a positive spin on such things but not anymore.

You have drummed for PROPAGANDA, ICEHOUSE, ALICE and MANDALAY as well as for Takahashi and Tsuchiya, while noted sticksman Gavin Harrison has cited you as one of his favourite drummers. Did the idea of session work ever appeal to you?

No, I wasn’t that versatile. I had my own way of doing things which meant that what I played wasn’t particularly universal and therefore the people that wanted to work with me did so because of the approach I took to drumming rather than fitting into place with a particular style of music. This isn’t good form for a session drummer.

You worked with John Foxx and Steve D’Agostino on ‘A Secret Life’. Are there any other established artists you would be interested in working with?

That project arose from meeting at a Harold Budd concert in which we all took part. I didn’t have much to do that with that particular project except to take the Budd concept further of creating ambient sounds on a gong. I’ve never really looked to seek out other artists to work with except for vocalists, and even then I’m not keen on going for high profile people (which is just as well because why would they?).

You’ve been with major record companies, run your own independent labels, used distributors and have now adopted Bandcamp as a sales outlet. What is the future for an artist in your position?

I will continue to make music because it’s not a job as such, and certainly not a hobby, it’s more of a need to be creative and find a balance in myself. I don’t know if a time will come when I no longer feel the need to do it, have to wait and see.

You blog quite regularly on your Sleepyard platform. How are you finding engaging with a fanbase via the joys of the world wide web and all that it entails?

It’s nice to communicate with people. Not having been ‘a front man’ in the true sense of the word, I’ve not done a great deal of press. The idea of projecting my persona and claiming ownership of any one project has never really appealed to me as it might to some, but being able to answer specific questions that people might be curious about can be a pleasant exchange and sometimes gives me a chance to realign history a little. That’s all.

Photography is still very much a part of your life and artistic expression…

I have an archive of images that I’ve only recently been exploring and thus put a book out. I do appreciate photography and think it runs in parallel to being creative musically as music and visuals both paint pictures and are emotive in different ways but can also work in collusion.

What’s next for you?

I’m working on project EXIT NORTH (with the Swedes) and quietly working on new material.

ELECTRICITYCLUB.CO.UK gives its grateful thanks to Steve Jansen

‘The Extinct Suite’ is available in CD and download formats from the usual retailers and direct from https://stevejansen.bandcamp.com/album/the-extinct-suite-2

The double vinyl LP edition of ‘The Extinct Suite’ twinned with ‘Corridor’ is available from https://stevejansen.bandcamp.com/album/the-extinct-suite-corridor-lp-edition

The double vinyl LP edition of ‘The Extinct Suite’ twinned with ‘Corridor’ is available from https://stevejansen.bandcamp.com/album/the-extinct-suite-corridor-lp-edition

Steve Jansen’s photo prints are available from https://www.thefloodgallery.com/

https://sleepyard.wordpress.com/

https://www.facebook.com/stevejansenofficial

Text and Interview by Chi Ming Lai

Photos courtesy of Steve Jansen

30th May 2017, updated 28th March 2020

Follow Us!